In the 1960s, Grimaud, a farming village on the Bay of Saint-Tropez, opened its doors to an architect seeking to break away from the trends of the time and build a tourist town counter to massively built-up seafronts. The dream was too good to last, and at present local authorities are faced with the threats of flooding, erosion and the privatisation of the coastline. In 2019 and 2020, a team of architecture students from ÉAV&T came to their aid. More details from Thomas Beillouin, architect and town planner, teacher-researcher at ÉAV&T.

François Spoerry’s dream

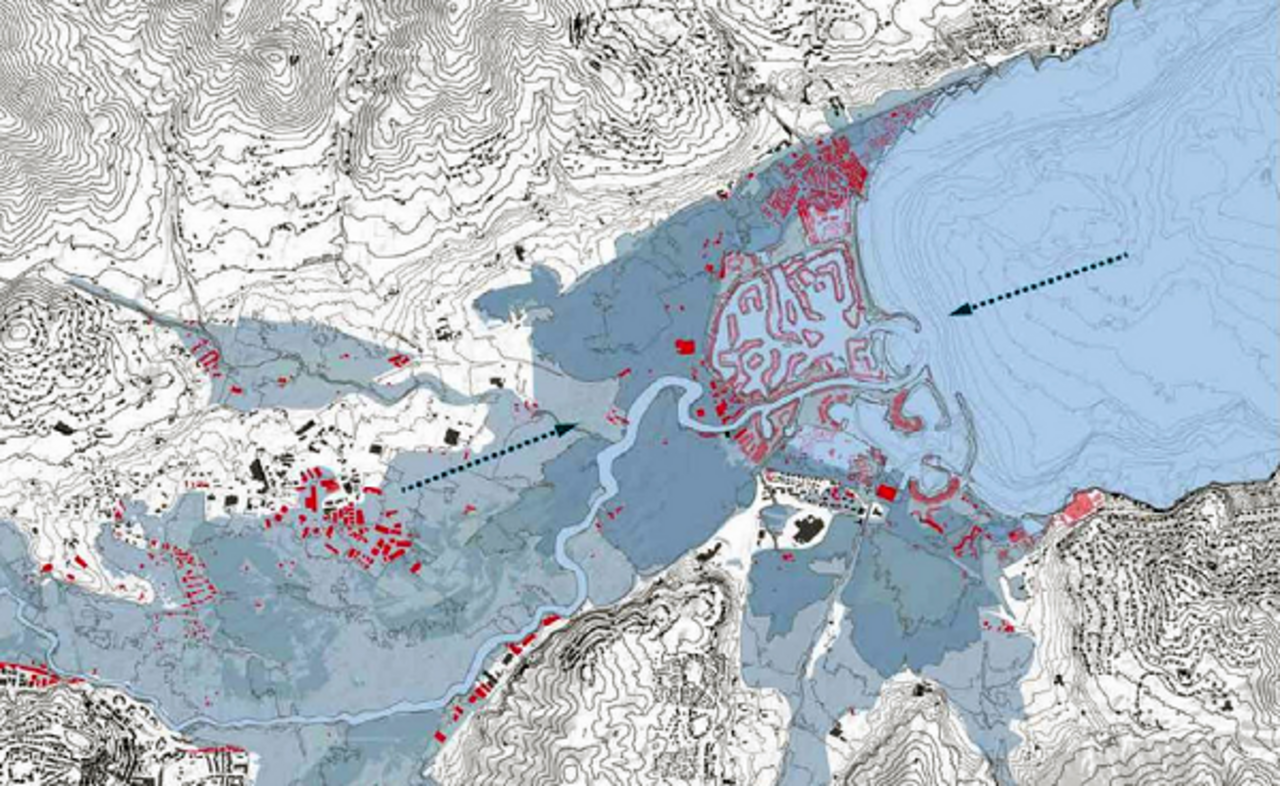

In 1964, Mulhouse-born François Spoerry, an architect renowned for his love of the sea and his numerous marina projects, bought marshlands in order to build his dream: the lagoon town of Port-Grimaud (located at the mouth of a river). This ensemble of 2,200 housing units inspired by vernacular architecture and designed on the model of the fisherman’s cottage, ran counter to the modernist canons of the concrete ensembles which sprawled along the post-war coastline. The town covered 75 hectares. With its small tile-covered houses built along 7 kilometres of canal ways, Port-Grimaud was a take on Venice with a Provencal twist. The architect imagined a pedestrian town which would restore a strong link between the land and the sea. The town, which is presently classified as Outstanding Contemporary Architecture, is a far cry from these initial intentions. It has become a vast co-ownership of secondary homes, the shops and craft-workers housed in the ground-level arcades are all geared towards tourism; access to this common heritage property is controlled by a security company and, around this gated community, none of the social housing initially planned came into being, due to opposition from the first owners. In addition to this failing from a social perspective, Grimaud is also facing environmental constraints. For Thomas Beillouin, Doctor of Architecture at Université Paris-Est, ‘It’s no coincidence that Port-Grimaud is out of synch with agricultural realities and climate issues; the original town centre overlooks a low-lying floodplain. At present, we must pinpoint the shortcomings of this form of town-planning and change paradigm.’ The coastline needs to reinvent itself for the 21st century.

The coastline, a land for architects

Storm Xynthia in February 2010 heralded a turning point in public policies and universities. In 2018, ÉAV&T participated in the creation of a chair associating schools of architecture, a design office and an inter-ministerial body. Entitled ‘The Coastline as a Project Ground’, it is coordinated by Thomas Beillouin: ‘We need to hear the voices of the various fields of the project, such as architecture, town-planning and landscape, with regard to coastal threats, an area dominated up to now by geography and geophysics.’ In 2019 a group of Specialised Degree (DSA) architecture & town-planning students from ÉAV&T were called on to carry out a study of Grimaud. In association with the Golfe de Saint-Tropez Community of Districts, Grimaud Town Hall and the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur DREAL (regional directorate for the environment, town-planning and housing), their task was to put forward solutions to adapt the region to coastline dynamics and enable inhabitants to cope better with its associated risks. For Thomas Beillouin: ‘The idea is to enhance this unique heritage while mitigating the errors of town-planning which ignores the ecological and social value of the region.’

In their study, published in 2020, the students proposed a new vision of the coastline and an approach to restore its depth, by relocating campsites away from the waterline, for example, or transforming agricultural pathways in to access lanes to the sea for soft modes. They designed light structures that can be dismantled, a ‘soft’ architecture in place of the solid buildings on the sea front. The lagoon city rediscovers its pedestrian vocation, opens to the public and restores its link to the water by adapting to the rise in sea levels. ‘The academic approach helps to shift boundaries and respond more freely to these prospective study orders’, Thomas Beillouin believes. For the students, this on-the-ground experience taught them how to establish a dialogue with local authorities and related technical departments. ‘Now it’s time for local powers to act’, the researcher in architecture adds.